‘John Bowes’ success brought significant prosperity to the Palmer shipyard, leading to the construction of several steamships in the early 1850s. Notable among them were ‘William Hutt,’ ‘Countess Strathmore,’ ‘Sir John Easthope,’ ‘Northumberland,’ ‘Jarrow,’ ‘Durham,’ ‘Phoenix,’ and ‘Marley Hill.

‘John Bowes’ had a remarkable working life spanning 81 years. Initially serving as a store vessel in the Crimean War, it underwent numerous name changes and survived multiple collisions. Interestingly, instead of carrying coal, it transported general cargo. Unfortunately, while sailing under the name ‘Villa Selgas,’ the ‘John Bowes’ met its tragic end in 1933 when it developed a leak off the northern coast of Spain. Thankfully, all crew members were rescued.

Flat-Iron Colliers

The Palmer shipyard introduced a ground-breaking design called the flat-iron colliers, which featured low superstructures and hinged funnels and masts. This innovative design allowed these ships to lower their structures and pass under the numerous bridges on the Thames River. Consequently, coal shipments could be transported further up the river, offering a convenient door-to-door service to the industry.

The ‘Westminster’ and ‘Vauxhall,’ launched in 1878, played a crucial role in transporting coal, with the ‘Vauxhall’ making around 60 trips per year, carrying approximately 1,000 tons of coal each time. However, due to the frequent voyages between the Tyne and the Thames,

The ‘Vauxhall’ experienced several accidents. One notable incident occurred in October 1888 when the ‘Vauxhall’ collided with the ‘Prudhoe Castle’ at the mouth of the River Tyne. Although the ‘Prudhoe Castle’ suffered significant damage, it fared better than the ‘Vauxhall,’ which sank but was later refloated.

In the latter part of 1853, a celebratory dinner was held at the Golden Lion Hotel in South Shields to commemorate the first engine built at the Palmer yard. The ‘Jarrow,’ launched early in the 1850’s, was the first ship fitted with this machinery. Throughout its lifetime, the ‘Jarrow’ proved its worth by delivering approximately 18,000 tons of coal to London.

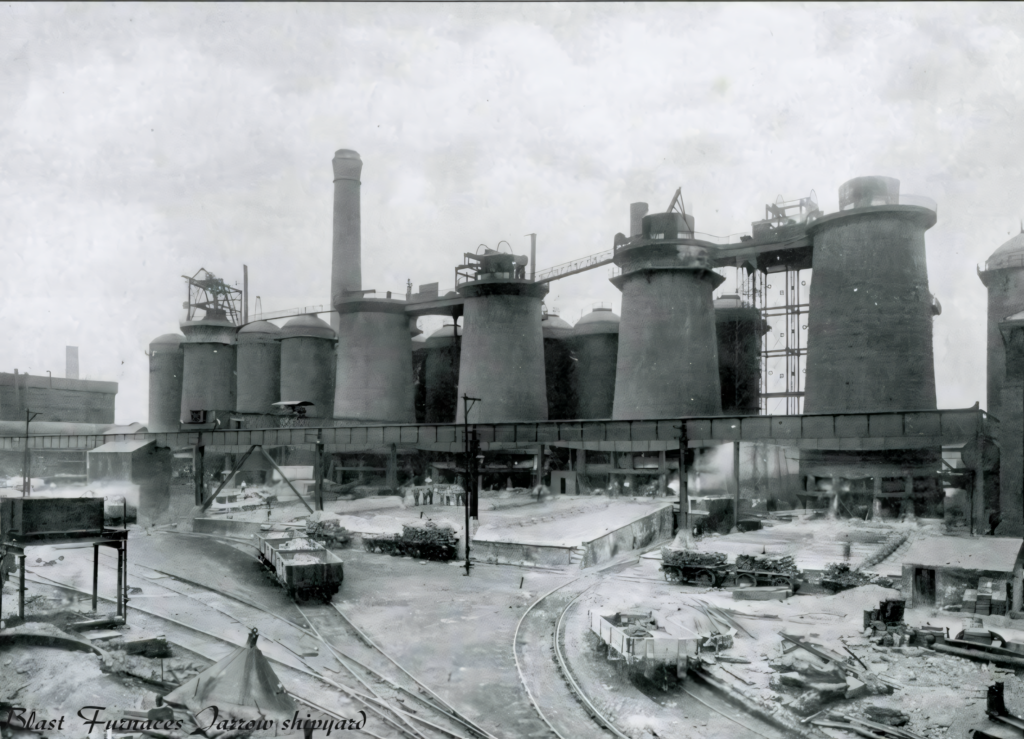

Blast Furnaces

In 1857, the Palmer shipyard expanded its operations to include blast furnaces, followed swiftly by rolling mills. To secure a reliable supply of ore for his blast furnaces in Jarrow, Sir Charles Mark Palmer acquired mining rights near Saltburn on the North-East Coastline. He set about constructing a harbor known then as Port Mulgrave, which he had built close to the mines, at a cost of some £30,000, this was in response to no suitable nearby port being available to safely load the ore onto his steamships destined for his blast furnaces in Jarrow.

Initially, Palmer’s ships were built of iron, but from 1880 onward, steel became the preferred material. The Albatross, the first steel ship constructed, was launched in January 1884 by Miss Price, daughter of John Price, the company’s general manager. By the late 1880’s, the Palmer shipyard boasted an impressive lineup of facilities, including an iron ore quay, blast furnaces, rolling mills, a foundry, boiler erecting shop, steelworks, dry dock measuring 440 feet, engine works, a smith’s shop, shipbuilding yard with eight berths, two jetties, additional workshops, and a 600-foot slipway for ship repairs.

Employment Peaked

The Palmer shipyard in Jarrow, under the leadership of Sir Charles Mark Palmer and his brother George, was more than just a place of work; it was a way of life, with its railway layout connected seamlessly to the main railway system, ensuring smooth transportation of goods and materials.

The shipyard thrived, and with each passing year, its workforce swelled, reaching a staggering 10,000 strong by the peak of 1927. The future looked bright, and the people of Jarrow had every reason to be proud.

From Prosperity to Despair

The once-thriving industry at the Palmer shipyard faced an unexpected downturn that left the people of Jarrow in despair, as their assured employment came to a standstill. This sudden decline left the proud men and women of Jarrow in despair, ultimately leading to what became known as the Jarrow March/Crusade.